Looming Deficits Present Opportunity to Find Solutions for California

Less than six months ago, California’s state legislature approved a record breaking $300 billion state budget. Within that total, and to finance most of the state’s ongoing operations, was a general fund allocation of $235 billion for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2023.

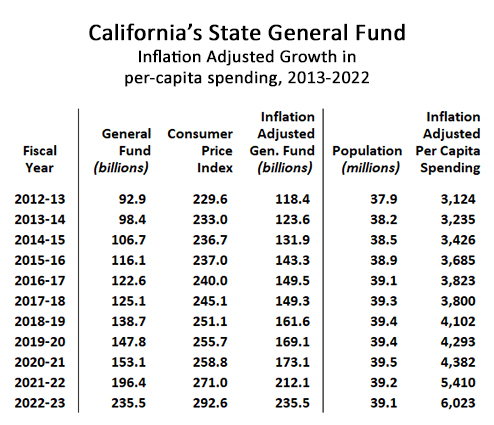

Record breaking budgets are nothing new. Only ten years ago, California’s general fund was $93 billion, which adjusted for inflation would be $118 billion in today’s dollars. Meanwhile, California’s population over the past ten years has only grown from 38 million to 39 million. This means that inflation adjusted per capita general fund spending in California has increased from $3,124 back in 2013, to $6,023 today. California’s state government is spending twice as much money today per resident as it did just ten years ago.

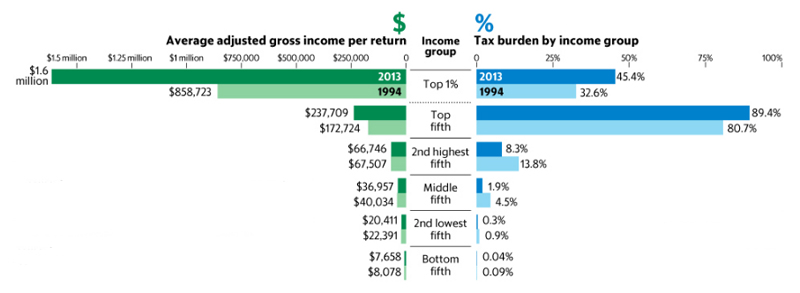

This explosion in spending has yielded dubious benefits. By nearly every measure, things are worse off today in California. Obvious examples include expensive and unreliable energy and water, failing schools, rising crime, unaffordable housing and college tuition, and an exploding homeless population, but that’s hardly the entirety of the worsening challenges facing Californians. The decade-long run of record tax revenue spawned an avalanche of new regulations, driving up prices, discouraging expansion of big business and driving small businesses under. Through its spending priorities California attracts the dependent and repels anyone striving for independence. It’s grotesquely inequitable.

This is the context in which to view the latest revenue projections coming from the nonpartisan Office of Legislative Analyst. The concern here should not be that our state budget for 2023-24 now faces a potential $24 billion deficit. The concern should focus on why there has been an explosion of state spending, yielding nothing but growing dysfunction.

As it is, LAO’s projection of a $24 billion deficit is a baseline case, relying on several assumptions that could go sideways, tumbling the actual deficit into much more troubling territory. For example, LAO acknowledges the likelihood of a deepening economic recession, but does not factor the impact of a recession into their tax revenue estimate. They write, “Were a recession to occur soon, revenue declines in the budget window very likely would be more severe than our outlook.” In the section of their analysis where LAO projects worst case scenarios, they project general fund revenue dropping as low as $180 billion in 2024-25, which based on merely maintaining the current general fund budget reflects a deficit of $55 billion.

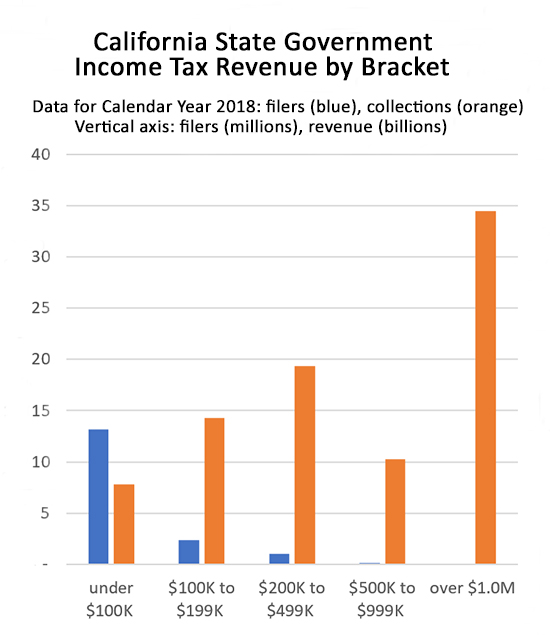

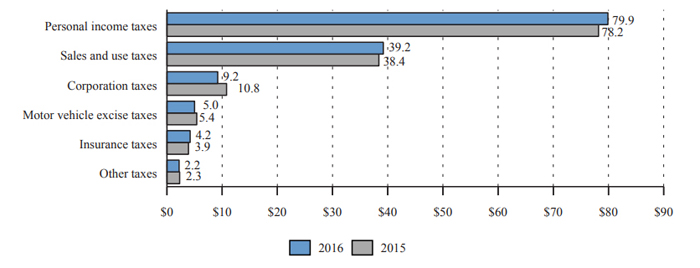

If the events of the past three years have taught us anything, it’s that consequences of pivotal events are often only obvious in hindsight. In June of 2020, did anyone really think that COVID shutting down half the economy would lead to a boom in tech company valuations? Did anyone at that time realize how uniquely beneficial the tech stock boom would be to California’s state general fund tax revenue? It’s easy today to look back and recognize the chain of causes, but it wasn’t easy to predict them when the COVID ordeal first began. It’s also easy, and probably accurate, to say that over this time period, the state legislature’s blithe ambition to make sure spending kept pace with revenue growth was blissfully unaware of just how improbable and fleeting the gift was that they were squandering.

Another lesson from the past three years, however, is to be wary of excessive pessimism. Unsustainable economic models work until they don’t work, and as long as the US Dollar is the least afflicted currency in the world and the US is the most secure investment haven in the world, and as long as inflation continues to reliably erode the principal value of a nominally exploding federal debt, massive deficit spending to stimulate economic activity may remain a viable strategy. If only more of that spending would be invested in practical infrastructure. Nonetheless, this could go on for decades. It could take forms we can only imagine. We simply don’t know.

The question therefore isn’t how to cut spending and raise taxes in order to balance the budget. The likely truth is that California’s state legislature is going to muddle through one way or another. The prevailing question should be how does California’s state legislature start to do the right thing instead of the wrong thing with all that money? They’ve doubled per capita spending in the last ten years, and ordinary hard working Californians can’t afford to live here any more. Clearly, so far they’re doing everything wrong.

LAO warnings of an impending general fund deficit are a good time to not only talk about how California’s state legislature is on the wrong course, but exactly how it can change its course. If you want to realign the state’s politics, it isn’t enough to say taxes, crime, and prices for everything are too high, and educational achievement and the supply of housing are too low. Propose concrete solutions. Very few Californians would mind paying their taxes if the state was affordable and effectively addressing the challenges of crime, homelessness, education, housing, water, transportation, energy, and education.

Solutions exist, but lack politicians with the courage to promote them and the charisma to effectively convince voters of their efficacy.

Offer state vouchers to parents to use to send their children to any accredited school, public or private.

Rescue public education by replacing woke curricula with classical education would save billions and rescue a generation from a failing system.

Fast track approval of nuclear power plants, natural gas fracking, and refinery expansions to force competition for energy and lower the prices for fuel and electricity.

Fund more water supply projects and practical freeway improvements, using tax and bond funds to yield long term economic dividends.

Approve housing developments in weeks instead of decades and reduce California’s absurdly overwritten building codes to lower the cost of housing.

Turn the timber industry loose again to thin California’s dangerously overgrown forests.

Build inexpensive minimum security facilities to incarcerate drug addicts and petty thieves to curb crime and end unsheltered homelessness. Use these facilities to teach inmates vocational skills so upon release they can fill hundreds of thousands of high paying construction jobs.

New solutions. An entire new alternative vision. This is the real discussion that California needs. Not just how to balance the budget. Rather, how to allocate the budget, and how to deregulate the economy. Where are politicians who are ready to step up with more than criticism of the failures of California’s one-party state, and offer solutions?

This article originally appeared in the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.