Letter to a State Worker

It must be tough for a California state worker to deal with the rising resentment of private sector workers. It must be easy to consider all of this some sort of plot by big business and billionaires to smack down the public sector workers, now that they’ve finished their nefarious beat-down of the private sector workers. There may be comfort in these notions, but little accuracy. Here are some thoughts for our state worker brethren to consider:

The average CalSTRS pension in 2010 for retirees leaving with 30+ years of service was $68,000 per year (ref. Government Worker Understates Average Pension). This benefit is extremely out of line with what is financially feasible. In the competitive, globalized private sector, the ability to retire before age 60 with an income of $68,000 per year requires amassing a huge amount of wealth. When savings accounts are paying interest of less than 1.0%, and the stock markets have been down for over a decade, might you not want to question the assumption that CalSTRS can earn 7.75% per year, long-term?

A self employed person in the private sector who manages to earn over $80K per year pays 53.25% tax on every extra dollar they make – 15% for employer and employee FICA and medicare, 28% federal, and 10.25% state. That doesn’t include property taxes or sales taxes, or the many taxes embedded in the typical utility and telecom bills. And, of course, if they don’t work, they don’t get paid. They are responsible for finding and paying for 100% of any benefits they enjoy including health insurance. And often, even if they are willing and able to pay the premium, they can’t find an insurance company who will cover them.

It is fine if you public sector workers need some time to accept the fact that your benefits are unsustainable. But to call those of us who have been coping with the impact of globalization and the collapse of the asset bubble for several years (if not decades) “haters,” or to encourage us to villainize big business and billionaires, does nothing to advance this discussion. Think about this:

1 – It is true that Wall Street special interests are to blame for much of our economic challenges, but your public sector pension funds are the biggest players on Wall Street.

2 – It is also true that monopolistic huge corporations are hurting the economic prospects for the rest of us, but you may not appreciate the difference between gigantic corporations who squelch competition and those emerging companies who disrupt the big corporations with faster, better and cheaper products who make our lives easier. And again, the presence of regulations tend to favor the monopolies more than the emerging companies – as do your pension funds.

3 – YOU are not bailing out Wall Street. Private sector taxpayers are footing that bill. When Wall Street conned the entire U.S. population and political leadership (it was totally bipartisan) into thinking we could drown ourselves in debt and hide that debt behind a bubble of phony, over-inflated assets as collateral, you benefited because your pension funds rode the wave of unsustainable growth that the debt created. Now the taxes paid by private sector workers pay for your pension, because Wall Street’s promises of high rates of return for your pension funds turned out to be false. And yes, you pay taxes. But for you to say that you pay taxes is sort of like the guy who stood inside a bucket and pulled on a rope hooked to the handle of the bucket, and wondered why he wasn’t able to levitate.

4 – Yes, in the old days everyone had a better pension. Are you kidding? Go back to pre-1999 payscales and pension formulas, retroactively, and you can keep your pension. It would not be insolvent.

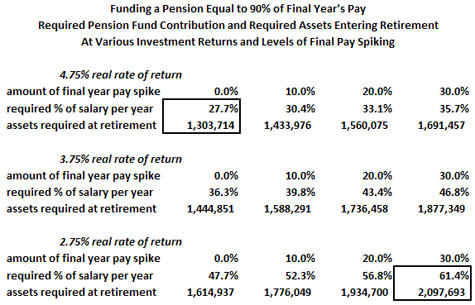

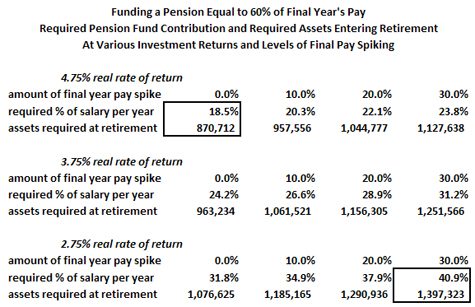

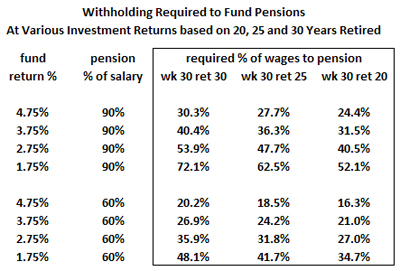

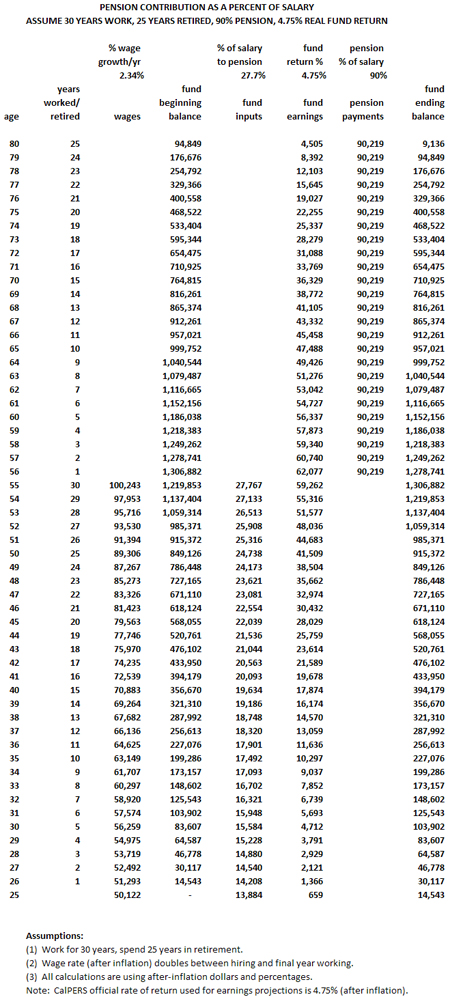

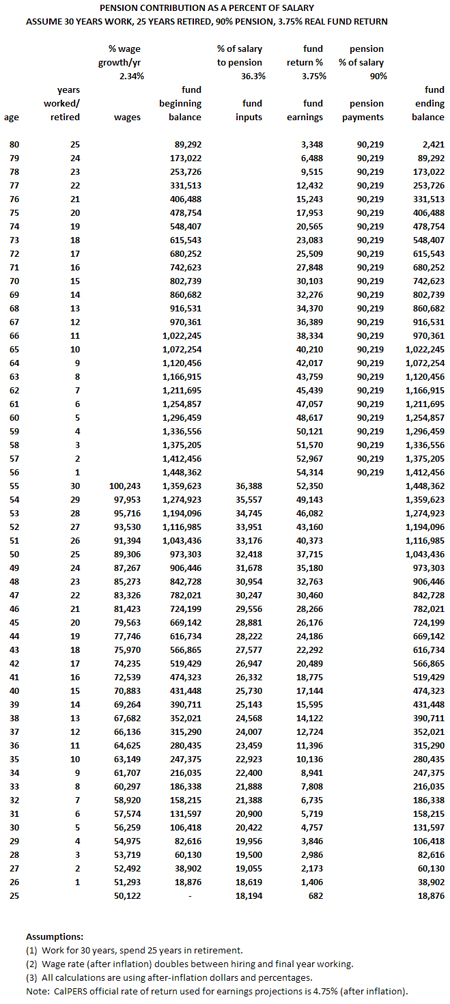

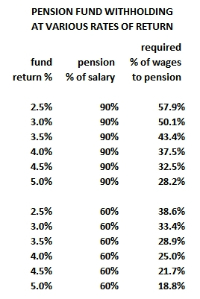

5 – You do NOT pay for most of your retirement. If, for example, you are getting 50% of your salary after 25 years in the form of a pension, that suggests you will spend at least one year retired for every year you worked. How much was withheld from your salary for your pension? 5%? 10%? To accrue at a rate of 2.0% per year, which is what you get in this example, even at CalPERS (and CalSTRS) increasingly preposterous claim that they can earn 7.75% per year over the long term, you would have to contribute 20% of your salary (ref. What Percent of Payroll Will Keep Pensions Solvent). Did you? And if that projected rate earned by CalPERS goes down only two points, to 5.75% per year (ref. CalPERS Projected Returns vs. Reality), you would have to contribute 36% of your salary – again, to get a 50% pension for 25 years after 25 years of work. Have you made these calculations? Have you contributed 36% of your salary into your pension fund?

What you really should think about, beyond these calculations which apparently escape most everyone except the Wall Street puppeteers who are laughing their heads off that they can gamble with taxpayer’s money as long as they buy off the public employees (who set policy through their unions who control the politicians in league with Wall Street lobbyists) with pensions that exceed social security by a factor of about 5x, is that it is impossible to extend pension benefits as generous as you are getting to everyone. It is completely impossible because (1) we have an aging population where more people are going to be retired, and (2) there isn’t enough “return on investment” in the world to relieve the taxpayers of covering most of the costs for these retirees.

You can blame Wall Street all you like. But Wall Street is YOUR benefactor, not mine. Your unions are collection agents for Wall Street pension funds.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.