The Role of Unions in a Perfect World

The optimal public policy regarding unions may not be realistic in states like California, but that shouldn’t prevent us from performing an occasional what-if. For anyone even slightly right-of-center, what unions have done to this state is a catastrophe. And even for those to the left-of-center, many are realizing, for example, that California’s failing system of public education is not because of inadequate funding, or due to the demographics of the students, but can be blamed primarily on a teachers union that has prioritized its political and economic agenda to the detriment of quality education.

It’s important, even if impossible to actually do anything today, to explore what might be the role of unions in California if the state legislature were ready to enact serious reform. Because not all unions are the same, and what has happened in California might happen elsewhere in the United States. We believe that preventing this is a nonpartisan imperative, and clarifying our intent may help prevent California’s plight from becoming America’s plight, and might even pave the way for eventual changes here.

This report is split into two parts, mostly to emphasize one main point, which is that public sector unions, representing government employees, are completely different from private sector unions, representing employees of private companies. It is necessary to expose once again how public sector unions, which should be illegal, have successfully pretended to face the same challenges and operate under the same constraints as private sector unions. Separately, it is necessary to explain how private sector unions have been corrupted, and have betrayed their own ideals and the aspirations of their members. We will begin with public sector unions.

Part One: Outlaw Public Sector Unions

Money doesn’t guarantee victory in political campaigns. For proof, look no further than Meg Whitman, the California billionaire who in 2010 squandered $179 million in her futile campaign to beat Jerry Brown and become that state’s next governor.

When money is married to institutional power, however, it makes all the difference. This is why, 10 years after the Whitman debacle, Mark Zuckerberg was able to influence the presidential election outcome in an unprecedented way by spending $419 million on “get out the vote” efforts via left-leaning nonprofit organizations that go far beyond “traditional campaign finance, lobbying or other expenses.” Whitman’s money paid consultants and bought ads on television. Zuckerberg’s money went to supplement the activities of election offices in swing states – election offices that employed workers represented by unions that overwhelmingly favor Democrats over Republicans.

This is a critical distinction. Imagine if a pro-Republican billionaire had, like Zuckerberg, poured hundreds of billions of dollars into “nonpartisan” nonprofit organizations that in-turn used that money to launch get-out-the-vote campaigns in areas heavy with Republican voters. What are the chances the election offices in these cities would have cooperated?

Consider Maricopa County in Arizona, the City of Philadelphia, or the City of Detroit. Election office workers in these cities, and many others around the country, are represented by AFSCME, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. In 2020, according to Open Secrets, 99.7 percent of AFSCME’s political contributions to federal election campaigns went to Democrats. Nationally, labor unions in 2020 spent a reported $1.8 billion on political campaign contributions, and of the public sector union share of that spending, 89 percent was spent to support Democrats.

Public sector unions don’t merely engage in political spending, their members occupy the bureaucracies that manage our elections. There are only five states that prohibit collective bargaining by public employees: Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The situation in Georgia exemplifies the power of these unions, because even there, while unions are not able to bargain, they are still permitted to recruit members and collect dues.

There is an inherent conflict of interest between the employees of government agencies and the interests of the general taxpaying public. When government programs fail, the natural inclination of a government employee is to protect their job security, which means they will claim not enough people were hired, not enough money was spent, and if more taxpayer dollars can get thrown at the problem, results will improve. This may or may not be true, but a taxpayer is much more likely to support programs that succeed, and to cancel programs that fail. From the perspective of a government bureaucracy, and the ambitions of the career bureaucrats that staff it, failure is an opportunity for growth and advancement.

This alone is reason enough to outlaw public sector unions. When a union agenda overlays onto what is already a built-in bias towards more government as reflected in the sentiments of government employees, that sentiment is buttressed with financial and political power, at the same time as it is corrupted further by the traditional union rhetoric that foments an adversarial relationship between employees and management. Which brings us to the next fatal flaw afflicting government unions: the fact that they elect their own bosses.

Political spending by government unions inevitably favors the candidates who will advocate for bigger government: more laws, rules, regulations, fines, fees, and taxes. That fulfills the ambitions of the union and its members: more money, more staff, more programs, translating into growth in membership dues and public employee compensation. When government unions negotiate for better pay and benefits, the politician sitting across the table knows that if they resist, they will be targeted for defeat in the next election. In any close race, and even in races where the incumbent would ordinarily have an advantage, the injection of union money will make the difference. There is no comparison in the private sector, where management is appointed by shareholders, and is retained or dismissed based on the success of the company, not the preferences of the unions representing its employees.

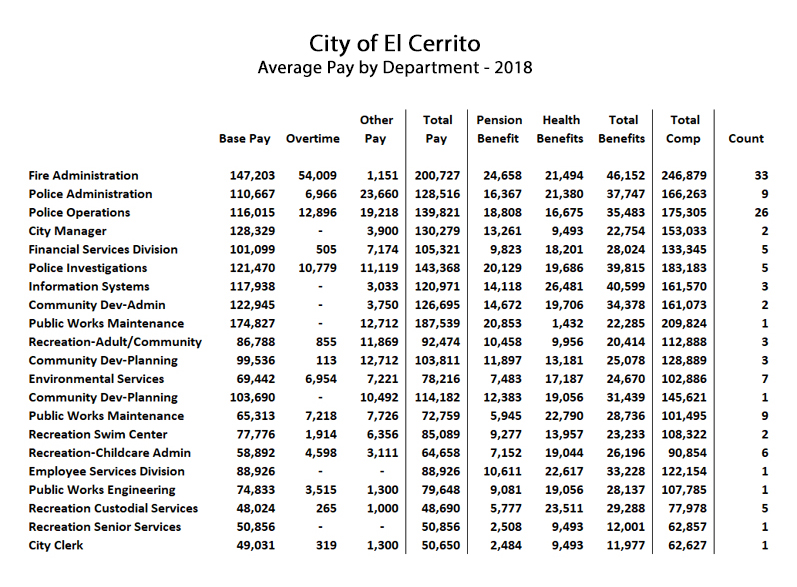

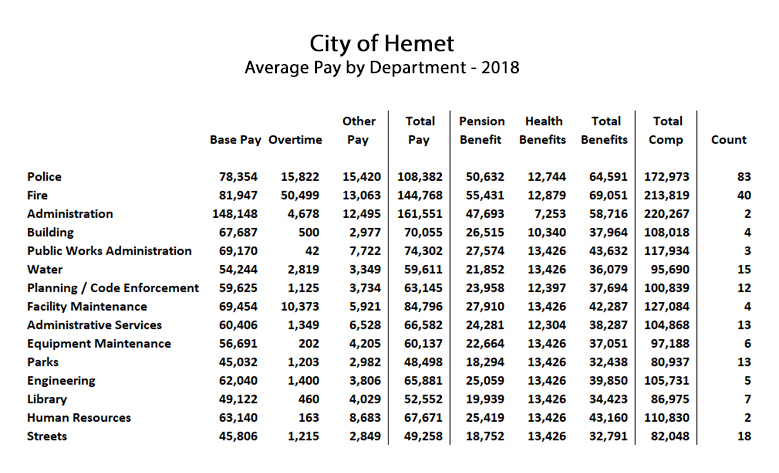

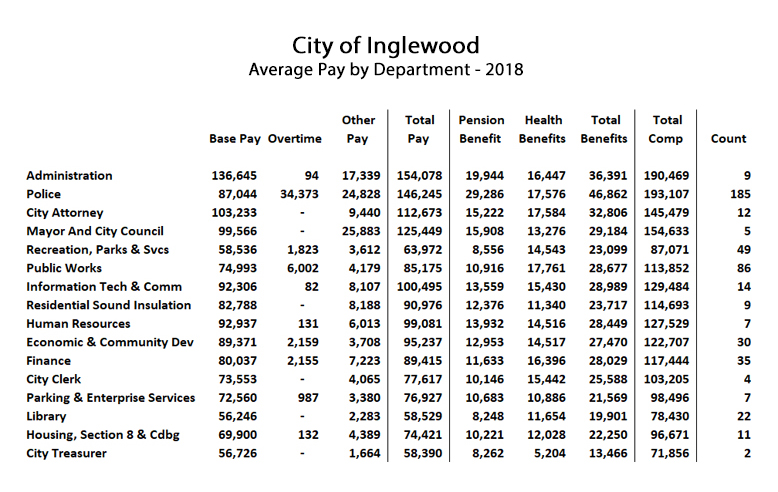

Unions in the public sector differ from private sector unions in another critical respect, which is that in their negotiations for better pay and benefits, they are not constrained by market realities. In the private sector, unions know that if they ask for too much, it will leave the company unable to compete, and this has a self-limiting effect on what they ask for. There is no such constraint on public sector unions. When they ask for increased pay and benefits, they know that the politicians they have elected will either raise taxes to grant these demands, or face defeat in the next election.

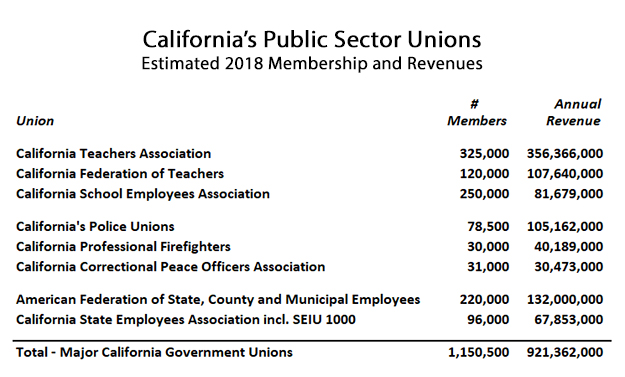

The consequences of allowing public sector unions to completely dominate a state can be seen in California, where public sector unions now collect and spend nearly one billion dollars per year in membership dues. The control this brings is easily verified. To fund the 2020 campaign to elect the Speaker of the California State Senate, Toni Atkins, every one of the top 10 contributors was a public sector union. For the Speaker of the California State Assembly, Robert Rivas, every one of the top 20 contributors was a public sector union. This dominance is seen across every elected office in the state.

In California, public sector union money is used either explicitly to fund political campaigns all the way from the governor and U.S. Senators down to every local elected position including school boards, city councils, county supervisors, water agencies, public utility commissions, transit districts, judgeships, etc., or is used to fund “nonpolitical” public education campaigns and “nonpartisan” get-out-the-vote campaigns. The result? California has the highest taxes, the highest cost-of-living, and the highest rate of poverty and homelessness in the nation. But for government unions, failure is success.

California is also the epicenter of high tech, and the ability of Google and Facebook to manipulate public opinion and voter turnout in elections is well documented, as is the propensity of these companies to support Democrats. But this behavior, decisive as it may be, would not be a match for the power of union-controlled government if it were out of alignment. Just as the unionized, overwhelmingly Democrat federal bureaucrats during the Trump administration actively thwarted his policy agenda and executive actions, if big tech were using its power to promote Republican candidates and causes, agencies, regulators, judges and politicians would swiftly find a way to stop them cold.

There is an innate incentive for government employees to want to grow government. This makes any political party or politician that is devoted to the principle of limited government automatically their enemy. To add to that inevitable and perennial conflict, the power of organized unions tilts the balance and rigs the game.

Public sector unions are one of the root causes of government overreach and inefficiency in America today. As long as these unions can use their financial and political power to serve the interests of government bureaucrats, proponents of limited government are fighting a nearly impossible battle. They should be outlawed.

Part Two: Reform Private Sector Unions

Unlike public sector unions, private sector unions have a vital role to play in American society. But these unions have become coopted by the same special interests they were originally formed to oppose. The political agenda of America’s unions is almost exclusively leftist, and being part of America’s institutional “Left” is not what it used to be.

For this reason, pressure from the outside, for example to require right-to-work protection for those workers who don’t want to be compelled to join a union, is not sufficient. Private sector union reform has to also come from within, and most likely from the grassroots members themselves demanding changes at the top. These members must recognize that the politics of unions in America today are not in their best interests.

The biggest misconception in American politics today is that the political Left is fighting corporate power. Leftists may still attack corporate profits and demand corporations pay their “fair share,” but on every major issue affecting the economic freedom and prosperity of working families in America, these presumed antagonists are actually in perfect alignment.

Labor unions, originally formed to defend the interests of workers, are no exception. Their decades of de-facto support for unrestricted immigration is a prime example. From the SEIU, “Stay strong against Trump’s wall!;” from the AFL-CIO, “oppose H.R. 2, the Secure the Border Act of 2023.” Rather than protect the interests of American workers by controlling the borders, unions demand something that is impossible to achieve when borders are overrun with millions of immigrants, a “universal social insurance safety net and strong worker protections that bolster the health, welfare and economic security of all working families.”

America’s unions deny one of the most basic of economic truths, that increasing the supply of workers will result in lower wages.

There’s another basic economic truth that eludes America’s union leadership, which is that there are two ways to secure the “economic security of all working families.” The first is to collectively bargain and when necessary strike for higher wages and benefits. But the other, which truly will benefit all workers, is to support policies that lower the cost-of-living. Towards this second goal, unions have been actively hostile, because they have accepted the “climate crisis” narrative.

There is irony in the SEIU’s official position, which states that “climate change is real and poses significant threats to people’s health and livelihood, and disproportionately affects working people, the poor and people of color.” They’re sort of right. But it isn’t climate change, but the policies implemented to supposedly mitigate it, which disproportionately harm working people and the poor.

The position taken by the AFL-CIO on climate change exemplifies how opportunism has replaced a concern for the welfare of all workers. A June 2022 convention resolution states, “In every forum, we will demand that clean energy technologies be mined, produced, constructed and operated under union contracts.” Just a month earlier, in May 2022, the AFL-CIO announced, “We’re here for the signing of the Project Labor Agreement between NABTU and Ørsted—the culmination of years of hard work on a game-changing partnership that will change the trajectory of the entire offshore wind industry.”

The trajectory, overall, goes something like this: We will negotiate project labor agreements that guarantee our members well paying jobs working on projects that will greatly increase the cost of energy in America. In the case of offshore wind, that cost became prohibitive, when in November 2023, Orsted, the largest offshore wind farm company in the world, ditched its two planned offshore wind projects along the south coast of New Jersey.

Earlier this year, in August, another giant wind farm company, Equinor, pulled out of the Trollvind project in the North Sea because of unforeseen challenges including “technology availability, time constraints, and rising costs that made the project commercially unsustainable.” Also in August, Equinor sought “a 54 percent increase for the price of power produced at three planned U.S. wind farms” off the coast of New York. In the face of a likely denial, Equinor announced it could cancel U.S. offshore wind projects. In November 2021, Equinor abandoned a 1.4 GW floating wind farm off the shores of Ireland.

Wind farm developments, costing hundreds of billions to build at scale, only make financial sense to developers if they’re awarded massive government subsidies. But for big labor interests, fleecing taxpayers and punishing ratepayers so multinational corporations can make billions in profits on offshore wind is of secondary concern, as long as union jobs are created. Offshore wind projects typify the synergy between government subsidies, mega-corporations, and big labor that is the true motivating force behind climate crisis policies.

In California, a state that has completely succumbed to climate crisis panic, the High Speed Rail project fulfills all these criteria. The state is well on the way to spending over $130 billion on a system with ridership projections that aren’t more than a rounding error in total air and vehicle miles traveled each year by Californians, but it delivers thousands of high paying jobs to unions and lucrative contracts to the corporations they work for.

If unions don’t start fighting for practical infrastructure projects that lower the cost-of-living, expect more of these boondoggles. Another union supported project that will squander hundreds of billions in subsidies and raise prices to consumers is “carbon capture.” In a nation where production of natural gas and hydraulic fracking are under relentless assault, and nuclear waste is the boogeyman of the century, the consensus between government, corporations, and big labor is that we need to pump literally gigatons of CO2 exhaust into underground caverns every year. Go figure.

The only explanation for what is an otherwise inexplicable alliance between big labor and big corporations is a shared preference for economic centralization. Corporations in America stopped believing in competition a long time ago, if they ever did. But the innate corporate drive to expand and monopolize markets was challenged and limited by the power of the American Left. Today that balance has been lost. After the anti-globalization marches of 2000, and the Occupy Movement starting in 2011, corporations realized they could coopt the Left by assimilating their agenda on the broad issues of diversity and the climate crisis. And as they must have known, this has actually worked to their advantage.

In both cases, new barriers have been erected to exclude emerging smaller competitors. In every industry, the burden of hiring based on race and gender quotas instead of competence, and the expense of operating an expanded human resources department to enforce these quotas and fulfill the new reporting requirements, has given very large companies a decisive advantage. Unlike smaller companies, they can spread the expense over a much larger base of revenue.

This is equally true with environmental regulations, where the overhead and investment and additional operating costs necessary to comply will destroy the financial viability of smaller companies, at the same time as the big corporations easily have the resources not only to comply, but to buy up the smaller companies and further grow their market share. As for “renewables,” the more they cost and the more access to conventional energy is restricted, the more money pours into the industry from customers forced to pay the higher prices. The idea that major energy companies oppose renewables is ridiculous. It is in their economic interests to see the price of energy go as high as possible.

Unions support corporate consolidation and centralization of economic power because higher wages and benefits for their members become part of the overhead that drives smaller, non-union companies out of business. Big companies with captive markets are able to offer the highest compensation packages to union workers, because they have eliminated their competitors and can therefore pass the increased costs to their customers.

For unions in the United States to once again fight for the interests of all American workers, they will have to recognize hard economic realities. An unlimited supply of new residents in America will either drive down wages or overwhelm the welfare state; both of these outcomes are undesirable. Current environmentalist policies are too extreme, and while they benefit corporations, government, and labor unions representing workers in certain heavily subsidized industries, they are driving the cost-of-living out of reach for the vast majority of American workers.

Delivering an optimal standard of living to all Americans is only possible with controlled immigration, practical infrastructure investments, merit-based hiring, a regulatory environment that doesn’t wipe out competition between corporations, and policies with respect to energy and the environment that don’t inflict economic harm on working families. Unions might also recognize that most “renewables,” certainly including wind energy, biofuel, and battery manufacturing, are devastating to the environment.

These are facts that unions must face, and the agenda that unions should adopt. Such a reform is unlikely, but possible if they return to their founding principles. If unions were to adopt these principles, it would not only benefit all Americans. It would also restore America’s strength and enhance America’s standing as an example and an inspiration to the rest of the world, and offer again a model for other nations to follow.

This article was originally published by the California Policy Center.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.