Citizen Reformers Set to Transform Oxnard’s Politics

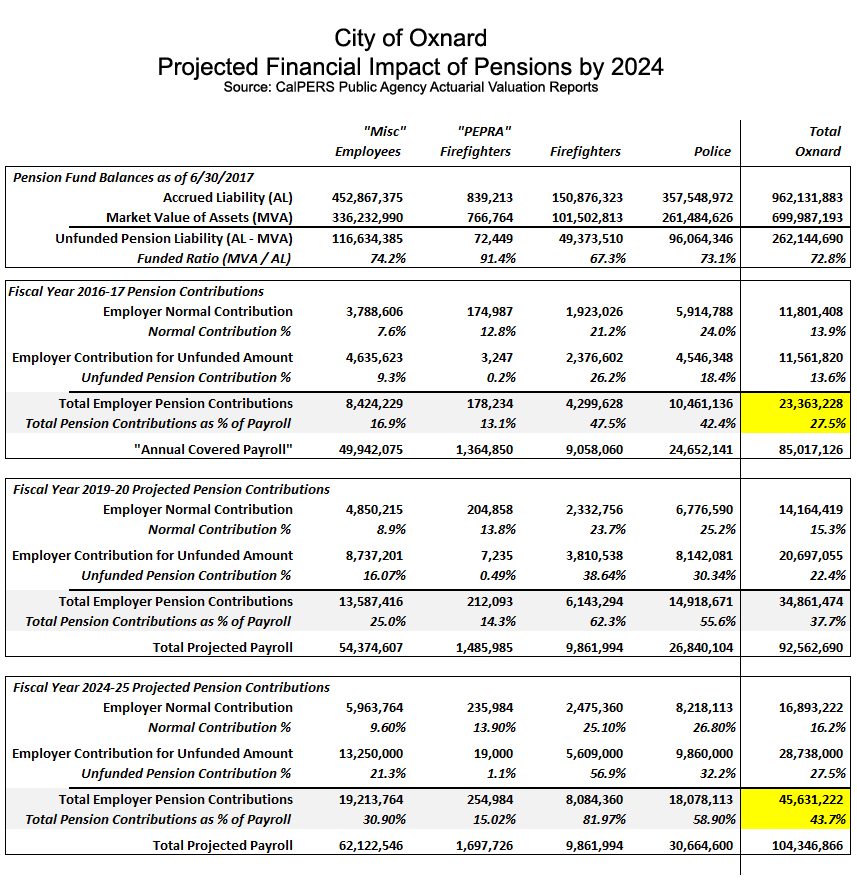

Oxnard has got a problem. The city’s contributions to CalPERS, which totaled $23 million in their fiscal year 2016-17, are going to increase to $45 million by 2024-25.

Where is this money going to come from? As reported last week, the “skyrocketing pension costs” have already led Oxnard’s Mayor to call for “painful cuts.” But if pension payments are set to double in just the next six years, where will all these cuts come from?

Meanwhile, in Oxnard, a small group of local activists, led by Aaron Starr, a local executive with a financial background including a CPA, are working to qualify five reform initiatives. If they gather the signatures required for each initiative, residents of the City of Oxnard will vote on them in November 2020.

The process of filing a citizens initiative is relatively straightforward. One reference is Ballotpedia, which provides a good summary of laws governing the local ballot measures in California.

In Oxnard, for example, there are 82,000 registered voters, and in order to place a local initiative onto the ballot, ten percent of registered voters have to sign a petition. In practice, it is advisable to collect 40-50 percent more signatures than the minimum necessary to qualify. For Oxnard, that would mean 12,000 gross signatures are necessary to qualify each ballot measure.

Citizen sponsored ballot measures to repeal local taxes or implement other reforms are common, but not as common as proposals and counter-proposals initiated by local city councils, school boards, and county boards of supervisors, to increase local taxes or authorize new borrowing.

For example, in November 2018, California’s voters were asked to approve 259 new local taxes, totaling an estimated $1.6 billion in new annual collections. At the same time, they were asked to approve 125 local bonds totaling $18 billion, which would add estimated annual repayments of $1.2 billion. Typically, around 70 percent of local tax increases and around 80 percent of local bond borrowings are approved by voters.

Nonetheless, some of the local initiatives to repeal taxes or implement other reforms have been successful. During this decade, San Jose and San Diego voters both voted to reform pensions, and despite bitter court disputes, much of those reforms have remained intact. In June 2016, local activists and Glendale residents William A. Taliaferro and John M. Voors successfully led a tax repeal effort in that city. And very recently, in April 2018, Sierra Madre residents Earl Richey and David McMonigle successfully led a tax repeal effort in that city.

What is unique about the Oxnard efforts is that five of them are being proposed at once. This is a model that might well be emulated by citizen reformers elsewhere in California. The cost to qualify one local reform initiative, vs. the cost to qualify five local reform initiatives, is not linear. Typically when a signature gatherer succeeds in getting a registered voter to sign one ballot petition, they’ll be willing to sign the rest of them. And when campaigning for reform initiatives, there might be a benefit to having a slate of initiatives. Voters might find it motivating to know that they have a chance to support a coherent package of several mutually reinforcing reforms that offer the potential for dramatic improvements to their local governance.

As summarized in this article in the Ventura County Star on May 4, 2019, the ballot measures that Starr and his colleagues are circulating for signatures are:

Oxnard Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, which would make the city treasurer, an elected official, the head of the finance department.

Keeping the Promise for Oxnard Streets Act, which would deny the city certain sales tax revenue if it fails to maintain streets to specific levels.

Oxnard Term Limits Act, which would limit the mayor and council members to no more than two consecutive four-year terms.

Oxnard Open Meetings Act, which would require city meetings to begin no earlier than 5 p.m. and allow public speakers no less than three minutes to comment.

Oxnard Permit Simplicity Act, which would reform the permitting system with training, new guidelines and an auditing process that would lead an applicant to obtain a permit in one business day.

One day? One day? In Sacramento County, there are business owners who have waited several months, and often over a year to get permits. Ditto for Sonoma County. Ditto for a lot of places in sunny California. As if business owners don’t have bank loans to service and employees to pay, while they wait for their permits.

As for pension reform? Perhaps Oxnard’s officials need to urgently explore ways to reduce the city’s obligation to CalPERS, since they may soon be more accountable than ever to the citizens they serve.

Clearly if all of these reform measures are passed by Oxnard’s voters, they will have a comprehensive impact. Imagine the impact of dozens, or hundreds of groups of local activists, applying this same strategy of filing multiple initiatives, in jurisdictions throughout California.

Title and Summary documents for the five proposed ballot measures in Oxnard are already publicly available (by the way, it is the city attorney, and not the initiative proponents, that prepares the Title and Summary). To download the official Title and Summary for each of these ballot propositions, click on the following links:

Oxnard 2020 – Finance – Ballot Title & Summary

Oxnard 2020 – Streets – Ballot Title & Summary

Oxnard 2020 – Term Limits – Ballot Title & Summary

Oxnard 2020 – Meetings – Ballot Title & Summary

Oxnard 2020 – Permits – Ballot Title & Summary

This article originally appeared on the website of the California Policy Center.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.