With light rail, high speed rail, and possibly passenger drones and hyperloop pods just around the corner, it’s easy to forget that the most versatile mode of transportation remains the common road. Able to accommodate anything with wheels, from bicycles and wheelchairs to articulated buses and 80 ton trucks, and ranging from dirt tracks to super highways, roads still deliver the vast majority of passenger miles.

As vehicles continue to evolve, roads will need to evolve apace. Roads of the future will need to be able to accommodate high speed autonomous vehicles. They will also need to be smart, interacting with individual vehicles to safely enable higher traffic densities at higher speeds. But can California build roads competitively? How expensive are road construction and maintenance costs in California compared with other states in the U.S.? How can California make the most efficient use of its public transportation funds?

PHYSICAL VARIABLES AFFECTING CONSTRUCTION COSTS

The Federal Highway Administration maintains a cost/benefit model called “HERS” (Highway Economic Requirements System) which they use to evaluate highway construction and highway improvement projects. One of the products of HERS is the FHWA’s most recent summary of road construction costs, updated in 2015. Its findings reveal both the complexity facing any cost analysis as well as the wide range of results for similar projects.

For example, on the FHWA website’s HERS summary page, Exhibit A-1 “Typical Costs per Lane Mile Assumed in HERS by Type of Improvement” data is presented in nine columns, each representing a typical project category for which the FHWA analyzes costs. They are: “Reconstruct and Widen Lane,” “Reconstruct Existing Lane,” “Resurface and Widen Lane,” “Resurface Existing Lane,” “Improve Shoulder,” “Add Lane, Normal Cost,” “Add Lane, Equivalent High Cost,” New Alignment, Normal,” “New Alignment, High.”

The FHWA then break their results in each of the nine project categories into two broad groups; rural and urban. Within each of those two groups, they offer the subgroups; “Interstate,” “Other Principal Arterial” (these two are combined in the “Rural” group), “Minor Arterial,” and “Major Collector.” This creates seven cost groups, each of which are then further split. For “Rural” categories, they split into “Flat,” “Rolling,” and “Mountainous.” For “Urban” categories, they split into “Small Urban,” “Small Urbanized,” “Large Urbanized,” and “Major Urbanized.”

To make a long story short, and to state the obvious, “cost per lane mile” is never one number. The FHWA’s HERS table, which itself is a reductive, arguably arbitrary summary, there are 252 distinct cost per lane mile estimates, 24 per project category. And within these nine categories, the range of costs is dramatic.

According to the HERS analysis, adding a new lane to an interstate on flat terrain in a rural area costs $2.7 million per lane mile. To do the same thing in a major urbanized area costs $62.4 million per lane mile, more than twenty times as much. Even minor projects display wide ranges in cost. Resurfacing an existing lane of a principal arterial in a flat, rural area costs $279,000 per lane mile. To do the same in a major urbanized area costs $825,000 per lane mile, three times as much.

The fact that topography, existing usage and population density affect road construction costs isn’t news. But the wide variation in costs that result from these physical variables compounds the other major factor affecting road construction costs, which is the political and economic environment of the states where projects occur. As will be seen, the FHWA compiles state by state data on road construction. This data, however, is apparently not sufficient to allow the FHWA to produce a HERS summary showing costs per lane mile by state.

EXAMINING FEDERAL DATA ON ROAD EXPENDITURES BY STATE

The FHWA Office of Highway Policy Administration does issue a highway statistics report, updated annually, that provides valuable per state data on highway mileage and transportation budgets. Their 2016 report is available but incomplete (still missing key tables such as “Disbursements by States for Highways”) so the 2015 report is still the most current. These tables are uniformly formatted and downloadable.

California’s Spending per Mile vs. Condition of Roads

An excellent analysis of FHWA data is produced every year by the Reason Foundation. Earlier this year they released “23rd Annual Highway Report,”ranking each state’s highway system in 11 categories, including highway spending, pavement and bridge conditions, traffic congestion, and fatality rates.” Highlights from this study can offer insights into how efficiently California is spending its highway dollars compared to other states through using the following logic: How does California rank in terms of how much it spends per mile, compared to how California ranks in terms of the condition of its roads.

Overall California is ranked 43 among the 50 states “Total Disbursements per mile.” California is ranked 41 in “Capital & Bridge Disbursements per mile,” 47 in “Maintenance Disbursements per mile, and 46 in “Administrative Disbursements per mile.” In terms of road condition, California is ranked 33 in “Rural Interstate Pavement Condition,” 45 in “Urban Interstate Pavement Condition,” and 46 in “Rural Arterial Pavement Condition.”

There’s not too much you can conclude from that in terms of efficient use of funds. Among the 50 states, California appears to be at or near the bottom 10% in spending per mile of road, and also in pavement condition.

In terms of cost-efficiency, among all states, this data suggests California is in the middle of the pack.

How Centralized Are California’s Road and Highway Agencies?

Within the FHWA data an interesting finding is the great variation between states in road mileage under state administration vs. road mileage under other administration – mostly cities and counties, but also federal. Only a few states, mostly the larger western states, have any significant mileage administered directly by the federal government – Alaska 14%, Arizona 22%, Idaho 16%, Montana 16%, New Mexico 16%, Oregon 28% and Washington 11%, and Wyoming 13%. Most all other states have low single digit percentages of roads administered by the federal government. The national average is 3%. California, only 6%.

State administration of road construction is higher, but still relatively low. The national average is 19% of road mileage administered by state agencies. California’s is significantly lower than average, at only 8%. Altogether, nationally, 78% of road mileage is administered by local agencies, mostly cities and counties. In California, 87% of road mileage is administered locally.

Before inferring too much from this fact, that road construction and administration is overwhelmingly ran by local agencies, FHWA funding data is useful. The data shows that total funding for roads in California in 2015 was $19.0 billion. Of that, 44% ($8.3 billion) was for “Capital Outlay,” which refers to new roads, new lanes on existing roads, new bridges, and bridge upgrades. The national average is 47% of all road spending on capital.

More to the point, the CalTrans budget in 2015 was $10.5 billion. According to the California Office of Legislative Analyst, that “includes $3.9 billion for capital outlay, $2 billion for local assistance, 1.8 billion for highway maintenance and operations, and $1.7 billion to provide the support necessary to deliver capital highway projects. How much of that was reported to the FHWA as part of the total $8.3 billion spent on capital? Certainly the $3.9 billion “for capital outlay.” Probably the “$1.7 billion to provide the support necessary to deliver capital highway projects”? What about the $2.0 billion of local assistance? For capital projects, it appears that between $5.6 billion and $7.6 billion of the total spending of $8.3 billion came from CalTrans.

The State of California’s role in total spending on road transportation is also reflected in the budget allocations in that year for the California Highway Patrol, $2.4 billion, which is included in the FHWA’s total for California, under “Law Enforcement” ($3.4 billion). It is possible, if not likely, that the state’s $1.1 billion for the Dept. of Motor Vehicles is included either in the Law Enforcement or Administration categories in the FHWA data, or allocated between them. Finally, the finance charges – interest payments and debt retirement totaling $1.5 billion – are not coming out of the budgets for the state’s transportation agencies, but some percentage of that total is paid by the state. Altogether it is likely that the State of California directly funded about $12 billion, roughly 63% of the $19 billion spent on road construction and administration in 2015.

Based on funding data, state agencies clearly play a central role in constructing and maintaining California’s roads.

California’s Spending per Lane Mile vs. Percentage of Lane Miles in Urban Areas

An interesting alternative way to get at how efficiently California uses its public transportation funds is to evaluate based on the expanded variables of total lane-miles instead of state administered road mileage, and total spending on roads by all public transportation agencies instead of just Caltrans. The rationale for using lane-miles relies on the assumption that it is more costly to build a mile of six lane highway (three lanes in each direction) than a mile of two lane road, meaning that lane miles provides a more meaningful denominator, if the numerator is total public spending on roads. The rationale for examining spending by all public transportation agencies relies on the assumption that many, if not most of the political and economic factors that govern road construction costs in California are common throughout the state, having the same effect on construction costs regardless of the funding source.

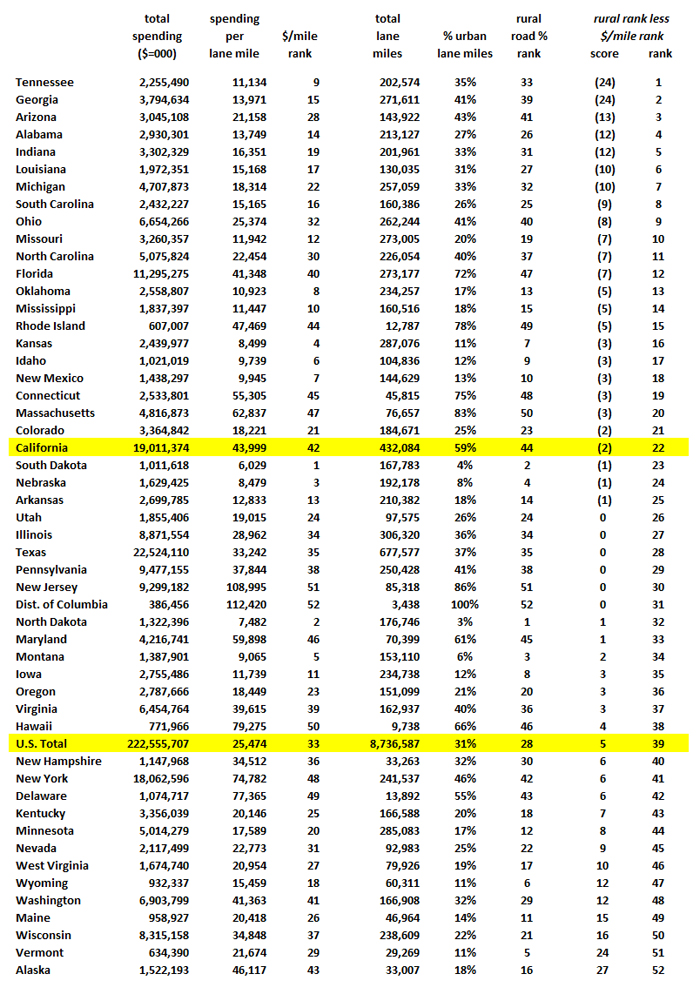

Using FHWA data on lane miles and total spending by state to calculate spending per lane-mile, California was found to average $43,999 in total spending per lane-mile. This ranks California 42 among all states. The national average is $25,474 in transportation spending per lane-mile. Put another way, for every dollar that, on average, is spent to build and maintain a lane-mile in the nation as a whole, California spends $1.73. This suggests that California is not spending its transportation funds nearly as efficiently as the most other states, but without considering other variables this is a misleading statistic.

One of the largest factors determining cost per lane-mile is urbanization. This is clearly evident in the previously mentioned FHWA website’s HERS summary page, Exhibit A-1 “Typical Costs per Lane Mile Assumed in HERS by Type of Improvement,” where costs per lane-mile are uniformly higher in urban areas, and in some cases far higher. As noted earlier, “According to the HERS analysis, adding a new lane to an interstate on flat terrain in a rural area costs $2.7 million per lane mile. To do the same thing in a major urbanized area costs $62.4 million per lane mile, more than twenty times as much.”

The idea that road construction costs more in urban areas can be attributed to several interrelated factors: Land values are typically greater in densely populated areas. Construction challenges are greater in urban areas where it is more likely that existing structures may have to be acquired and demolished to permit road construction or widening. Labor costs are typically higher in urban areas. Urbanized regions also are likely to have more local restrictions on development, leading to more costly permitting processes and higher fees. There are other key factors influencing road construction costs – for example, climate and topography – but urbanization is easily quantifiable and likely the most significant of them.

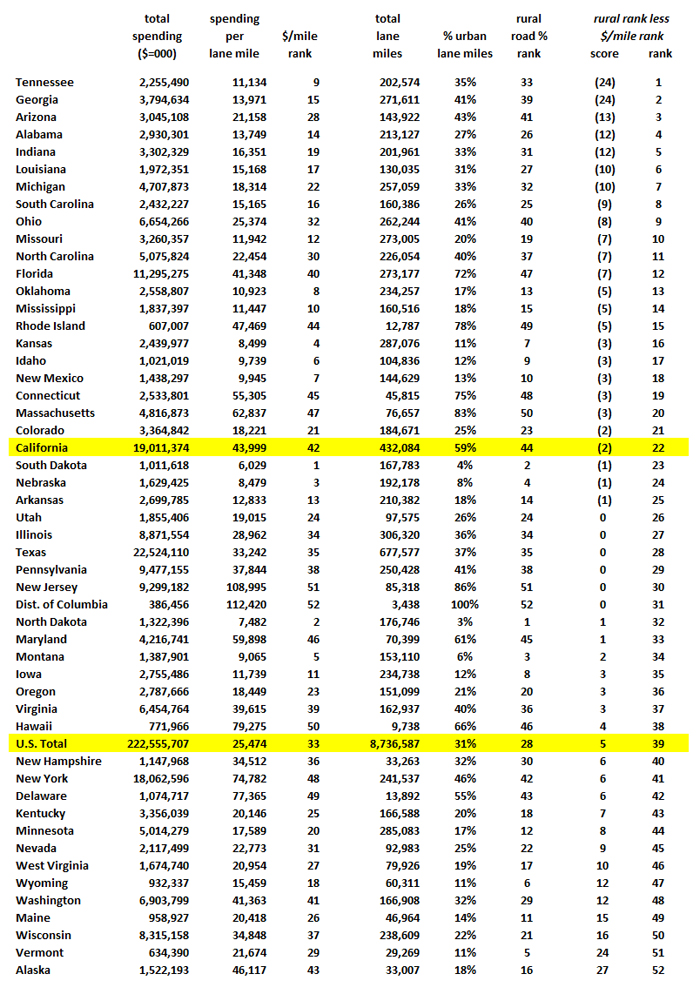

For this reason, the following chart includes not only spending per lane-mile by state, but also includes the percentage of lane-miles, by state, that are in urban areas. Here, California distinguishes itself as one of the most urbanized states, having 59% of its lane-miles within urban areas. The national average, by contrast, is almost half that; only 31% of the nation’s lane miles are located in urban areas. Tracking these two rankings, spending per lane-mile and percentage of urban lane miles, permits an illuminating comparison. If one assumes there is a correlation between cost per lane mile and percentage of lane miles in urban areas, then how a state ranks in one should be similar to the how it ranks in the other.

Six states conform exactly to this assumption. Utah, for example, is the 24th most expensive state to construct roads per lane-mile, and it has the 24th most rural percentage of roads. Similarly, Illinois has a $/mile rank of 34, and it has a rural road % rank of 34. Texas, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the District of Colombia all have $/mile rankings exactly equal to their rural road % ranking. Five more states have a deviation between their $/mile rank and their rural road % rank of only one. California’s is only two – it is ranked 42 in its cost per lane mile, making it quite expensive relative to most states, but it is ranked 44th in its percentage of lane-miles in rural areas, meaning it is one of the most urbanized states.

The final set of columns on the chart, on the right, show a score for each state based on the rural road percent ranking less the $/mile ranking. If the score is negative, that means the state spending on lane miles ranks better (less per mile) than its rank based on its percentage of rural lane-miles. In other words if the score is negative, that means the state is spending less per lane mile than one might expect based on their level of urbanization, and if the score is positive, the state is spending more per lane mile than one might expect based on their level of urbanization.

Once again, California is in the middle of the pack.

Spending per Lane-Mile by State; Percentage of Urban Lane-Miles by State

(Source: Federal Highway Administration, 2015)

If one assigns any credence to these rankings, it presents interesting questions. Why is it that states like Georgia and Tennessee, which are relatively urbanized, are among the top performers in terms of being able to cost-effectively construct and maintain their roads? In the case of Tennessee, it isn’t as if they’ve neglected their roads, they are in the top ten in all three FHWA measurements of pavement condition. Georgia’s scores on pavement condition put them in the middle among states.

In some of the poorly ranked states, topography and climate may be factors. Alaska, the one of the least urbanized states nonetheless is one of the most expensive states to build and maintain roads, which should come as no surprise. Most of the states with low scores have harsh climates.

A final note regarding California – while it shows a high correlation between its cost per lane-mile and its level of urbanization, it does not score well in the three pavement condition indexes; 33 out of 50 for rural interstates, 45 out of 50 for urban interstates, and 46 out of 50 for rural arterial roads.

California can do better.

OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Federal data indicates that while California scores poorly compared to other states in terms of road conditions, California also spends less than other states in terms of expenditures per lane mile. Considered in isolation, those two facts only suggest that California is using its transportation funds no more and no less efficiently than the average state. While federal data also indicates that California, overall, spends nearly twice as much per lane-mile as the national average, California is also more heavily urbanized, and normalizing for that reveals again that California is being roughly as cost effective in its use of transportation dollars as the average state.

When factoring in the condition of California’s roads, however, which are near the bottom in pavement condition indexes, California is not using its transportation dollars as well as it could.

Anecdotally, literally everyone surveyed – and we talked with representatives from dozens of agencies, research firms, and transportation agencies – agreed that per mile road construction costs are higher in California than most other states. But the federal data we had access to does not offer documentary proof of that, and Caltrans, despite numerous attempts, could not produce data on per mile construction costs that could be compared to national averages.

The lack of transparency, the complexity, and the subjective nature of any resulting analysis makes it difficult to assert with any certainty where California falls relative to other states – it is either somewhat below average, or far below average, but making that call requires a level of evidence and clarity that is simply not available. Ultimately it does not matter where California falls in that continuum, because regardless of how efficiently California spends their public transportation funds per lane mile of new or upgraded roads, there are ways to improve. The following recommendations were heard repeatedly, from contractors, trade associations, and researchers familiar with the topic. The first two in particular:

(1) Reform CEQA

CEQA, or the California Environmental Quality Act, is a “statute that requires state and local agencies to identify the significant environmental impacts of their actions and to avoid or mitigate those impacts, if feasible.” While the intent behind CEQA is entirely justifiable, in practice it has added time and expense to infrastructure projects in California, often with little if any actual environmental benefit. An excellent summary of how to reform CEQA appeared in the Los Angeles Times in Sept. 2017, written by Byron De Arakal, vice chairman of the Costa Mesa Planning Commission. It mirrors other summaries offered by other informed advocates for reform and can be summarized as follows:

- End duplicative lawsuits: Put an end to the interminable, costly legal process by disallowing serial, duplicative lawsuits challenging projects that have completed the CEQA process, have been previously litigated and have fulfilled any mitigation orders.

- Full disclosure of identity of litigants: Require all entities that file CEQA lawsuits to fully disclose their identities and their environmental or, increasingly, non-environmental interest.

- Outlaw legal delaying tactics: California law already sets goals of wrapping up CEQA lawsuits — including appeals — in nine months, but other court rules still leave room for procedural gamesmanship that push CEQA proceedings past a year and beyond. Without harming the ability of all sides to prepare their cases, those delaying tactics could be outlawed.

- Prohibit rulings that stop entire project on single issue: Judges can currently toss out an entire project based on a few deficiencies in environmental impact report. Restraints can be added to the law to make “fix-it ticket” remedies the norm, not the exception.

- Loser pays legal fees: Currently, the losing party in most California civil actions pays the tab for court costs and attorney’s fees, but that’s not always the case with CEQA lawsuits. Those who bring CEQA actions shouldn’t be allowed to skip out of court if they lose without having to pick up the tab of the prevailing party.

(2) Restructure Caltrans

Caltrans currently outsources only about 10% of its work. Despite repeated attempts to legislate changes that would require Caltrans to use contractors to lower costs, no action has been taken. In a report prepared in 2015 by state senator Moorlach, the failure of California’s legislature to implement reforms is described: “In previous administrations, Governor Schwarzenegger pushed for an 89/11 ratio and could not achieve it. Even Governor Brown proposed a reduced ratio that was rejected by the Legislature.”

By maintaining permanent engineering staff instead of contracting, whenever projects are concluded these engineers are often idle until another project comes along. The Legislative Analyst’s Office in 2015 reported that there were 3,500 of these positions created for programs that have expired, requiring an extra $500 million each year.

The advantage of contracting out engineering work isn’t merely based on more efficiently allocating personnel to projects to avoid down time. When Caltrans does the designing, then puts the project out for bids, the contracting companies have to conduct redundant design analysis in order to prepare their bids. This also contributes to increased costs which are passed on to the taxpayer as well as extra time. In moving to a system where Caltrans just specifies the project goals and lets the contractors prepare competitive bids based on in-house designs, the taxpayer saves time and money. Ways to restructure Caltrans might include:

- Immediately increase the ratio of contracted work from 10% to 20%.

- Permit the headcount of in-house engineers at Caltrans to reduce through retirements and voluntary departures, systematically increasing the ratio of contracted work as the number of Caltrans in-house engineers decreases. Set a goal of at least 50% contracted work within five years.

- Abolish the current requirement that the state legislature has to approve any projects that are contracted by Caltrans instead of designed in-house.

(3) Decentralize and Innovate

On the FAQ page for Elon Musk’s Boring Company, the following innovations are proposed to lower the cost of tunneling by a factor of between 4 and 10: (1) Triple the power output of the tunnel boring machine’s cutting unit, (2) Continuously tunnel instead of alternating between boring and installing supporting walls, (3) Automate the tunnel boring machine, eliminating most human operators, (4) Go electric, and (5) Engage in tunneling R&D. More generally, on that FAQ page the following provocative assertion is made: “the construction industry is one of the only sectors in our economy that has not improved its productivity in the last 50 years.”

How can California use public transportation dollars to nurture innovation that will deliver more people to more places, faster, safely, for less money? One way would be to nurture competition by nearly eliminating Caltrans. Why should one state agency control nearly two-thirds of the funds for road construction and maintenance in California? Why not reduce Caltrans to a couple dozen administrators to handle federal regulations and direct federal funds and move all road work, expansion and maintenance to the counties? The counties can conform to a general state plan, but there’s no reason to have a state bureaucracy any more when the counties can be challenged to be more efficient, effective and non-duplicative in their work.

Imagine the innovation that might come out of Santa Clara County, where stretches of roadway could be immediately prioritized to add smart lanes where autonomous cars – including mini-buses and share cars – can operate safely at much higher densities and speeds. Imagine the innovation that might come out of Los Angeles County, where entire transit corridors could have congestion greatly relieved because thousands of cars are being swiftly and safely transported from point to point in underground tunnels. Imagine the innovation that might come out of San Francisco, where congestion pricing completely eliminates their chronic gridlock, or out of Orange County, where private investors team up with public agencies to use roboticized equipment to perform heavy road construction at a fraction of the cost for conventional processes?

Why not decentralize transportation management in California and turn the counties into laboratories of innovation?

(4) Expand Into the Vastness of California

It is an accident of history that California is so densely urbanized. Most metropolitan regions on the east coast, developed gradually over three centuries or more, have thousands of square miles of spacious suburbs, and tens of thousands of even more spacious expanses of moderately settled lands on the edges of remaining wilderness areas. California, in stark contrast, has nearly 18 million people residing in greater Los Angeles and over 7 million people residing in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. If you add residents of the San Diego region and Sacramento regions, you account for 32 million out of a population of 39 million. And yet all of California’s urban areas, the most densely urbanized in the nation, only constitute five percent of its 163,696 square miles! The math is compelling – you could settle ten million people in four person households on half-acre lots and it would only consume 1,953 miles. Double that for roads, parks, commercial and industrial space, and you are still only talking about urbanizing another 2.4% of California’s land. The idea that we cannot do this is preposterous.

The cost of infrastructure, roads in particular, is much higher in urban areas. So why not expand along the nearly empty Interstate 5 corridor, creating new towns and cities that are spacious and zoned to never become congested? Why not upgrade I-5 to accommodate high speed smart vehicles that provide nearly the speed of high-speed rail, while preserving the point-to-point convenience that only a car can offer? Why not expand along the entire fringe of California’s great Central Valley, where currently thousands of square miles of cattle rangeland are being taken out of production anyway? Why not build more roads on this raw land, bringing down the cost both for roads and the homes that will be built around them?

(5) Change the Conventional Wisdom

California’s policymakers have adhered increasingly to a philosophy of limits. Urban containment. Densification. Less energy use. Less water consumption. Fewer cars and more mass transit. But it isn’t working. It isn’t working because California has the highest cost of living in the nation. Using less energy and water never rewards consumers, because the water and energy never were the primary cost within their utility bills – the cost of the infrastructure and overhead was the primary cost, and those costs only go up with renewables. Cramming home construction into limited areas not only destroys the ambiance of existing neighborhoods, but simply cannot increase the supply of homes enough to lower the cost.

There is a completely different approach that would cost less and improve the quality of life for all Californians. Without abandoning but merely scaling back the ambition of new conservation and efficiency mandates, free up funds to build safe, generation III+ advanced nuclear reactors. At the same time, construct desalination plants on the Southern California coast, enough of them to supply the entire Los Angeles basin with fresh water. Instead of mandating water rationing for households, put the money that would have been necessary to retrofit all those homes into new ways to reuse water and capture storm runoff.

Paying for all of this wouldn’t have to rely exclusively on public funds. Private sector investment could fund most of the energy and water infrastructure. Water supplies could be even more easily balanced by permitting water markets where farmers could sell their water allotments without losing their grandfathered water rights. If the permit process and mandated design requirements were reduced, builders could carpet former cattle ranches with new homes, sold for a profit at affordable prices.

CONCLUSION

This is the final segment of a four part excursion into California’s transportation future. In each section the same themes emerged: It isn’t just what gets built to serve future Californians, it’s how cost effectively the money is spent. Innovation and regulatory reform – CEQA in particular, but also repealing SB 375, AB 32, and related anti-growth legislation – together have the potential to lower the cost of infrastructure, transportation in particular, by at least 50%.

California’s current policies have stifled innovation and created artificial scarcity of literally every primary necessity – housing, energy, water and transportation. Each year, to comply with legislative mandates, California’s taxpayers are turning over billions of dollars to attorneys, consultants and bureaucrats, instead of paying engineers and heavy equipment operators to actually build things.

The innovation that persists despite California’s unwelcoming policy environment is inspiring. Right here are the pioneering companies that will deliver flying cars, commercial access to outer space, breakthrough modes of transportation such as hyperloop and urban tunnels. Right here are the companies that will deliver self-driving cars, cars on demand, high-speed smart cars. These things will happen within a time frame that is, by the standards of human history, breathtakingly short. And with the right assortment of pro-growth policies in place, more of them will happen right here.

California’s transportation future cannot be predicted with any certainty. If the past few decades have taught us anything, it is that innovation routinely delivers products and solutions that nobody could have possibly imagined. But it is a reasonably safe bet that the common road is the most useful mode of transportation infrastructure for which public policy can risk public funds. A flat surface where wheeled conveyances of every conceivable design can all travel from point to point, clean, smart, versatile, sustainable, and fast.

* * *

Edward Ring co-founded the California Policy Center in 2010 and served as its first president.

California’s Transportation Future, Part One – The Fatally Flawed Centerpiece

California’s Transportation Future, Part Two – The Hyperloop Option

California’s Transportation Future, Part Three – Next Generation Vehicles

REFERENCES

[1] Federal Highway Administration – Highway Economic Requirements System

[2] Office of Highway Policy Information – Highway Statistics 2015

The FHWA’s annual highway statistics report is actually a series of tables, uniformly formatted and downloadable as Excel files. For this report, the following tables were downloaded and consolidated:

[2-A] Selected measures for identifying peer states

[2-B] Disbursements by States for highways

[2-C] Length by ownership

[2-D] Estimated lane-miles

[2-E] Disbursements by States for State-administered highways

[2-F] Total disbursements for highways, all units of government

[2-G] Estimated lane-miles by functional system

[3] Reason Foundation – 23rd Annual Highway Report

[4] California Office of Legislative Analyst – The 2015-16 Budget: Transportation Proposals

[5] California Office of Legislative Analyst – The 2014-15 Budget: Capital Outlay Support Program Review

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.