Government Worker Understates Average Pension

Today’s Sacramento Bee featured a viewpoint column entitled “Pension ‘Reformers’ distort facts on benefits.” The column was written by Martha Penry, “a special education teacher’s assistant in the Twin Rivers school district.” Not disclosed in the article was the fact that Ms. Penry is also a high ranking public employee union official, as evidenced by her membership on the CSEA Board of Directors.

In her column Ms. Penry accuses “pension busters” of overstating the cost of pensions and the amount of the average pension. She claims that “three quarters of CalPERS retirees collect yearly pensions of $36,000 or less.” What Ms. Penry does not do, however, is acknowledge that the average she is referring to includes retirees who didn’t work full time, or who didn’t work much more than five years (the minimum vesting period for a pension), or who retired decades ago when pay rates and pension formulas were still fairly reasonable.

A more honest assessment of the average pension has to examine rates for people who are retiring now, under today’s pay scales and pension formulas, who have worked their full careers in government service. Here is the most recent information, drawn directly from the annual reports of Cal STRS and CalPERS:

From the CalSTRS Annual Report, page 135:

CalSTRS participants who retired during the 12 months ending June 30th, 2010 (the most recent data), earned pensions as follows:

25-30 years service, average pension $50,772 per year.

30-35 years service, average pension $67,980 per year.

35-40 years service, average pension $86,736 per year.

From the CalPERS Annual Report, page 151:

CalPERS participants who retired during the 12 months ending December 31st, 2009 (the most recent data), earned pensions as follows:

25-30 years service, average pension $53,182 per year.

30+ years service, average pension $66,828 per year.

When one considers that the highest Social Security benefit possible, for people earning over $125,000 per year, is only $31,000, starting at age 68, it boggles the mind that anyone can suggest that reducing pension formulas for California’s state workers will risk “forcing retirees into poverty.” When government workers spend an entire career in government service, they earn pensions that are literally triple (or more) what they might have expected to receive from social security.

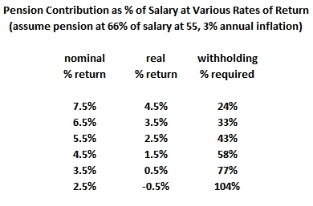

A related point Ms. Penry makes regards not the scale of the pensions, but the amount paid into pensions. She writes “public employee pensions amount to just 3% of California’s budget.” This is also grossly misleading. To dive into the numbers and better understand why that number is far, far too low, refer to “How Rates of Return Affect Required Pension Contributions,” “Why Real Rates of Return Must Fall,” and “California’s State AND Local Personnel Costs”

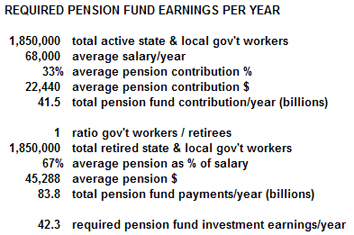

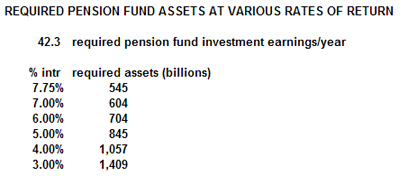

An equally relevant (and faster) way to sanity check Ms. Penry’s “3%” figure, however, is to consider not what California’s taxpayers are paying today into Wall Street pension funds for their government workers, but what taxpayers will pay in the future if reforms aren’t made. There are 1.85 million state and local government employees in California. As they retire they are replacing people who retired when pay scales and pension formulas were far more sustainable. Using an average career of 30 years and an average retirement of 20 years, we are on track to have 1.25 million retired state and local workers collecting, on average, $60,000 per year in retirement pension payments. That equals $75 billion per year. Shall the taxpayers, who will collect an average social security benefit of $15,000 per year, really be called upon to make up a difference of that magnitude when Wall Street returns fail? Because that process has already begun.

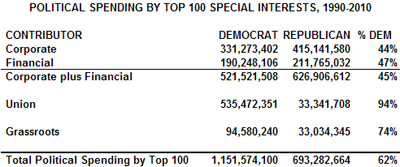

Ms. Penry got one thing right in her column today – reducing pension benefits being paid to former, current and future government workers is not going to solve California’s budget woes all by itself. The base rates of pay for most government workers will also have to be reduced. It is ironic that the unions representing government workers seized the opportunity when the economy was enjoying the phony real estate boom (and the internet bubble before that) to negotiate dramatic increases to their compensation packages, yet are blind to the need to reduce those packages now that the bubbles are burst.

Anyone who believes that calls to lower pension benefits for government workers is just “pension busting,” is invited to review the data presented here and in related posts. By pretending the “average” pension includes part-time workers, workers who only logged a few years in government service, and people who retired long before pension benefits were inflated beyond sustainability, it is Ms. Penry who is distorting the facts.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.