Funding Social Security vs. Public Pensions

In a previous post “Social Security vs. Public Pensions,” source data is presented to document the following reality in America today: Given a similar salary history, a non-safety public sector employee will collect a defined benefit pension approximately triple what they would have collected under social security, and a “safety” public sector employee will collect a defined benefit pension approximately 4.5 times what they would have collected under social security. This post is to explore how feasible it is to fund social security vs. public sector pensions.

As will be shown, the notion that social security is on the verge of insolvency, or will ever be on the verge of insolvency, is complete nonsense. In stark contrast, however, based on quantitative facts that are relatively easy to extract and analyze, public sector pensions are glaringly unsustainable and they are already grossly insolvent. To compare public sector pensions to social security in order to justify federal deficit spending to bail out public sector pension funds – rather than dramatically reduce their benefit formulas – is entirely fraudulent. Here’s how we get to these sweeping conclusions:

The social security fund has been described as a “ponzi scheme,” suggesting that it can only remain solvent if the new entrants who work and pay into the system fund the retiring beneficiaries who collect payments from the system. But this ponzi scheme metaphor quickly breaks down. First of all, a ponzi scheme typically implies an eventual return of principal to the investors, whereas social security only promises a defined – albeit modest – retirement annuity. Therefore if the people entering the system as workers can provide sufficient cash to fund the retirees who are collecting from the system, there is no danger of insolvency. You can call this a virtuous ponzi scheme, or abandon the metaphor altogether. It isn’t really a valid metaphor.

The valid concern about social security is based on the possibility that as the American population ages, the ratio of workers to retirees will inevitably drop, as baby boomers age and as average lifespans increase. But if the data is examined critically, this concern, at least in America, is overstated.

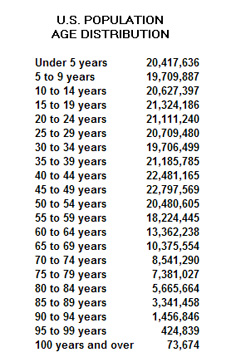

According to information found on the U.S. Census Bureau’s table “National Population Age Estimates,” summarized on the above table, there is clearly a large number of Americans who are about to become senior citizens, and consequently the number of senior citizens in America is going to nearly double over the next twenty years. But this data shows something else quite encouraging – the American age demographic is not about to invert, wherein the number of old people begins to significantly outnumber the number of young people. Remarkably, when examining each five year age group in America, nearly every one of them, from those under five years old through those in the 55 to 59 year age category, have almost exactly twenty million people. This not only demonstrates conclusively that America’s age demographic is simply transitioning from a pyramid to a column, and not inverting, but that it is easy to project retirement populations well into America’s future. Such an even stream of population age groups ascending America’s age continuum is a serendipitous reality – our age demographic is not inverting, it is normalizing – we are achieving a stable and sustainable population. To understand what this means for social security and public sector pensions, examine the next table (numbers are in thousands):

According to information found on the U.S. Census Bureau’s table “National Population Age Estimates,” summarized on the above table, there is clearly a large number of Americans who are about to become senior citizens, and consequently the number of senior citizens in America is going to nearly double over the next twenty years. But this data shows something else quite encouraging – the American age demographic is not about to invert, wherein the number of old people begins to significantly outnumber the number of young people. Remarkably, when examining each five year age group in America, nearly every one of them, from those under five years old through those in the 55 to 59 year age category, have almost exactly twenty million people. This not only demonstrates conclusively that America’s age demographic is simply transitioning from a pyramid to a column, and not inverting, but that it is easy to project retirement populations well into America’s future. Such an even stream of population age groups ascending America’s age continuum is a serendipitous reality – our age demographic is not inverting, it is normalizing – we are achieving a stable and sustainable population. To understand what this means for social security and public sector pensions, examine the next table (numbers are in thousands):

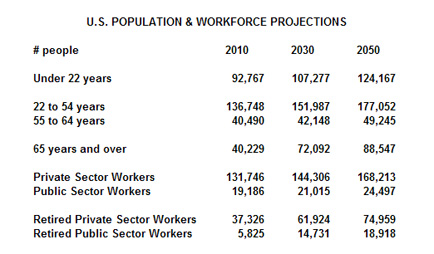

Using information from the U.S. Census Bureau’s table “Projections of the Population by Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2010 to 2050” (ref. 2nd link), and making some assumptions based on the earlier data that indicates an even stream of aging Americans – i.e., about 20 million people in each five year age group – it is reasonable to infer the above projections. That is, there are currently about 93 million Americans who have not yet entered the workforce, there are 137 million Americans between 22 and 54 years old, 40 million between 55 and 64 years old, and 40 million who are 65 years old or older. Using the same data, inferences can also be made for 2030 and 2050. As the table indicates, the population of all age groups increases over the next 20 to 40 years, with the largest increase among the 65 and older group. But the table also shows the number of people over 65 remains relatively stable between the years 2030 and 2050, which reflects the encouraging fact that Americans are replacing themselves, unlike many other developed nations.

Using information from the U.S. Census Bureau’s table “Projections of the Population by Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2010 to 2050” (ref. 2nd link), and making some assumptions based on the earlier data that indicates an even stream of aging Americans – i.e., about 20 million people in each five year age group – it is reasonable to infer the above projections. That is, there are currently about 93 million Americans who have not yet entered the workforce, there are 137 million Americans between 22 and 54 years old, 40 million between 55 and 64 years old, and 40 million who are 65 years old or older. Using the same data, inferences can also be made for 2030 and 2050. As the table indicates, the population of all age groups increases over the next 20 to 40 years, with the largest increase among the 65 and older group. But the table also shows the number of people over 65 remains relatively stable between the years 2030 and 2050, which reflects the encouraging fact that Americans are replacing themselves, unlike many other developed nations.

The data to project the total number of full-time workers in America is derived from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “Occupational Employment Projections 2008” table, indicating there are 151 million workers in the U.S. currently, or about 85% of the working age population. The number of government workers in America is derived from U.S. Census Bureau data, adding up their reported Federal, State, and Local tallies, and indicates there are 19 million public sector workers in the U.S. today. Using subtraction, the above table infers there are 132 million private sector workers in the U.S. today. It is important to note that in the context of calculating the solvency of social security vs. public sector pensions, 19 million public sector workers is a very conservative number, because it doesn’t include career military personnel, nor does it include millions of public utility workers who often enjoy retirements outside of social security, calculated instead using the same formulas as public sector pensions.

Based on the percentage of active public sector workers vs. private sector workers – adding one key assumption, that the ratio of government workers per capita has gone up 50% in the past 40 years – the 2010 retirement populations of government workers and private sector workers are also inferred on the above table. In reality, the 2010 numbers are not crucial, because it is the future solvency that is of concern. In this, the numbers are again quite conservative, because they assume the ratio of public employees vs. private sector employees remains constant, i.e., 11% of the working age population work for the government, and 74% of the working age population work in the private sector. Assuming the public sector workers retire on average at age 55, and the private sector workers at age 65, by 2050, the number of retired private sector workers will double, while the number of public sector workers will nearly triple. This disparity is explained based on two differentiating factors – the increase in government workers as a percent of the total workforce over the past generation, along with the earlier retirement of government workers compared to private sector workers. But when this headcount disparity is combined with the huge financial disparity between public pensions and social security, there is a dramatic compounding effect, as shown on the next table.

Using data from the same sources referenced above, the average annual earnings of private sector workers in the U.S. is currently $29K per year, and for public sector workers it is $52K per year. If one assumes these averages correspond to wage-earners at the mid-point of their career, which the even-streamed (neither pyramidal nor an inverted pyramid) age demographic of the American workforce does suggest, then the average earnings of someone in their final year of employment can be inferred using the Social Security Administration’s “Benefit Calculator’s” (ref. item 4) “relative growth factor” of 2.0%. That is, the average worker receives an increase to their earnings, after inflation, of 2.0% per year (all figures here are using 2010 dollars, which is to say they are real, or after-inflation figures). To estimate the final salary of a private sector worker, their average salary is multiplied by 1.02^20, implying a 40 year career, and for the public sector worker, their average salary is multiplied by 1.02^15, implying a 30 year career. From these inputs, the conclusions fall out via simple arithmetic, and they are staggering.

Using data from the same sources referenced above, the average annual earnings of private sector workers in the U.S. is currently $29K per year, and for public sector workers it is $52K per year. If one assumes these averages correspond to wage-earners at the mid-point of their career, which the even-streamed (neither pyramidal nor an inverted pyramid) age demographic of the American workforce does suggest, then the average earnings of someone in their final year of employment can be inferred using the Social Security Administration’s “Benefit Calculator’s” (ref. item 4) “relative growth factor” of 2.0%. That is, the average worker receives an increase to their earnings, after inflation, of 2.0% per year (all figures here are using 2010 dollars, which is to say they are real, or after-inflation figures). To estimate the final salary of a private sector worker, their average salary is multiplied by 1.02^20, implying a 40 year career, and for the public sector worker, their average salary is multiplied by 1.02^15, implying a 30 year career. From these inputs, the conclusions fall out via simple arithmetic, and they are staggering.

Right now, using these assumptions, our 5.8 million public sector retirees, representing 14% of the retired population, collect $245 billion in retirement pensions, whereas social security recipients, representing 86% of the retirement population, collect $553 billion in social security payments. The average social security payout is based on the Social Security Administration’s “Estimated Retirement Payments Chart,” applied to the projected average final salary of a private sector worker – using the average final salary (social security formulas are progressive, unlike public sector pensions, meaning the less you make, the higher percentage of your final salary you will receive in social security), this equates to $15K per year, or 34% of their final salary. The average public sector employee’s retirement pension payout is based on 2% per year times a 30 year career, applied to their projected average final salary – this is $42K per year, or 60% of their final salary.

Adding this all up, the ratio of total private sector payroll to total social security payouts is quite interesting in 2010 – at 14%, it suggests that social security today is breaking even, since 14% is what employers and employees together are currently contributing to social security. In turn, when looking at 2030 and 2050, the ratio of total social security payments to total private sector payroll does go up – but only to 22%, and it stabilizes there, reaching that level in 2030 and not increasing at all between 2030 and 2050. For social security to remain solvent in 2030 and beyond, the employer and employee contributions to social security will need to increase by 4% each, from 7% to 11%. Alternatively, the $104K cap on social security withholding can be raised, or there can be means testing, or other slight reductions to social security benefits, or there can be a slight increase to the age at which a worker becomes eligible for social security. Or a combination of all of these. The point is this: Social security can remain solvent with relatively minor and incremental tweaks. Social security is not about to go insolvent, and it never will.

When one examines public sector pensions, however, the opposite is painfully evident. Estimated total public sector pension payouts already are 25% of total public sector payrolls. By 2030 they will be 57%, and by 2050 they will be 62%. Equally dramatic is the projected absolute dollar amount that will be paid out in public sector pensions in comparison to social security – by 2030 social security will pay out $918 billion and public sector pensions will pay out $620 billion – 67% as much money for 24% as many people – and by 2050 social security will pay out $1.1 billion and public sector pensions will pay out $796 billion – 72% as much money for 25% as many people. At the rate we are going, public sector pensions, serving less than 20% of all retired Americans, are going to cost American taxpayers nearly the same amount in absolute dollars per year as social security payments, serving the other 80% of Americans. This is grotesquely unfair and ridiculously unsustainable. To compare social security, which can easily remain solvent, with public sector pensions which are already insolvent and are headed for utter collapse, is completely absurd.

Defenders of public sector pensions point out the fact that public sector pensions are invested, and therefore yield investment returns, which therefore compensates for what would otherwise be their financial shortcomings. Problems with this argument abound – first because pension funds will not generate the returns in the future that they generated in the past – read Pension Funding and Rates of Return, The Razor’s Edge – Inflation vs. Deflation, Pension Rhetoric vs. Pension Reality, Sustainable Pension Fund Returns, California’s Personnel Costs, Maintaining Pension Solvency, and Real Rates of Return, to name a few, to understand why the public employee pension funds have been overestimating how much they can earn on their funds. But more fundamentally, why are public employees entitled to see their pension fund contributions invested into the private sector, when private sector employees see their social security contributions held in a zero-interest trust? You can argue which is better or worse – I would suggest it is dangerous, for a variety of reasons, to throw this much money into passive private sector investments and that all taxpayer supported retirement annuities should be self-funded via current collections (the virtuous ponzi scheme) – but whatever one may conclude, there is no reason taxpayer funded retirement accounts should not be managed in the same manner for all Americans.

If you have waded through all these numbers, it is important not to miss the point. Social security and public sector pensions are not similar at all. The challenges facing social security are easy to address, whereas the challenges facing public sector pensions are dire, and cannot be solved unless either dramatic benefit cuts are implemented or massive tax increases are enacted. In the interests of the financial security and economic future of America, if not in the interests of equity in retirement for all American workers, the choice between benefit cuts vs. tax increases should be obvious.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

What I find most perplexing is that when the public safety employees retirement contribution was increased by Gov. Gray Davis to 3% with eligibility at 50 years old, this change was made retroactive in most bargaining units. If my plumber knocked on the door and asked for more money for services rendered last year, I’d have to tell him to go pound sand! Why wasn’t the change made applicable only on future earnings and flexibility maintained so that modifications could be made subject to changes in the financial health of the fund and of the municipalities?

The time is long overdue for California to follow the lead of Oregon and adopt a hybrid plan. Cease payments into defined contribution plans while honoring the obligation already earned and fairly negotiated. Establish a defined contribution program and make future payments for all employees, new and existing, with a possible exception for those retiring within one year, into these accounts. Make them self directed so the employee has the power, opportunity, responsibility and risk management to choose investments as is done in the private sector. Though new contributions into defined benefit programs would cease as would time in service credits, those that retire and are vested in the defined benefit plan would continue to receive disbursements from that plan in addition to the separate value they accumulate in their defined contribution account. Quite honestly, a properly managed investment account would yield more value to the employee with less expense to the public than the current system. Also, the full value of the account would be assignable to the employees beneficiaries.

Pitzkes: Thank you for your thoughtful comment. First of all, the “retroactive” pension benefit increases are being challenged in court, as they should be, and it is quite possible they will be nullified, as they should. And going forward, programs such as what you describe are reasonable and financially sustainable compromises. But I don’t agree with you that the employees will necessarily see their pension funds perform better under their own management, and through their own contributions. The public sector pension funds that currently manage the retirement assets of public employees are assuming rates of return that are totally out of touch with market realities. The irony is profound – of course in a debt-saturated world you are NOT going to see rates of return (adjusted for inflation) of 4.75% per year, but that is what CalPERS, to use a huge example, claims their funds will generate, year after year, decade after decade, after inflation. It is preposterous.